The Wood report of 2014 [1] rightly placed the emphasis on “far greater constructive collaboration between operators“ in the UKCS across the business life-cycle. Collaboration is an integral part of day to day petroleum exploration which works so long as it doesn’t compromise enterprise confidentiality. Collaboration through data exchanges are tightly controlled as much by perceived quid pro quo enterprise transactions as the avoidance of perceived anti-trust behaviours. Exploration risk can also be mitigated by broadening the portfolio with additional assets via swaps or new block additions - assuming no risk dependencies exist between the new and the old assets [2], which may involve a minimal degree of knowledge sharing. Such transactions are closed forms of collaboration between carefully selected entities, with clear value of information controls to protect intellectual property. Open collaboration however, whether through an exchange of data or knowledge, is a completely different transaction and one that challenges conventional views of enterprise driven dynamics. There is no question that enterprise driven principals are key to unlocking frontier, emerging and core basins, providing the engine for essential investment and value creation. But when a petroleum system approaches its perceived “end-of-life”, jumps in value require leaps in perception rather than data [3]. This is when collaboration through a more open exchange of knowledge potentially becomes a new value-driver but it requires a conscious shift in enterprise dynamics which are usually opportunity driven [4]. Incremental volumes add significant value to tired settings with high exploration maturity, partly because of the extra production flowing through existing infrastructure. Just as valuable to operators are the incremental savings in “money of the day” brought about by delaying decommissioning of the same infrastructure.

Connected Thinking

Evaluating exploration opportunities often involves the recognition of knowledge gaps both real and perceived. How those gaps are identified and bridged determines if an opportunity is one that reinforces your strengths or exploits your weaknesses as an enterprise. We call those knowledge gaps “white space”. Simplifying the scope (and to avoid accusations that ignorance is scope), there are four types of white space in petroleum exploration: physical white space (gaps in data), technical white space (gaps in data quality), intellectual white space (gaps in play-based thinking) and organisational white space (gaps in business focus). Each is associated with varying degrees in exploration maturity (Fig. 1) but the key to unlocking what remains of prolific petroleum systems like the North Sea, which have been delivering value for decades, is intellectual as well as organisational white space. Intellectual white space exists because we have become so focused on extracting value with diminishing returns from bread-and-butter plays, that we have become perceptually blind to new play opportunities. In effect, we have forgotten how to think outside the play. We know this is true because the North Sea continues to deliver surprises in areas that were thought to have been well picked over (e.g. Brae, Buzzard, Johan Sverdrup etc…). Surprises that also fail to deliver the extra running room because we have made incorrect assumptions about how they really work. New data are undoubtedly continuing to squeeze new value from the North Sea (e.g.NFE around Beryl) and new thinking is emerging (viz. injectites) but there is arguably no shortage of connected data in the North Sea, maybe just a shortage in connected thinking. Understanding which component of white space needs to be overcome to add value in exploration materially changes how you deploy resources to achieve it. Invading intellectual white space is about connecting knowledge to deliver a common understanding of residual value or “yet-to-find” (YTF).

Experimenting with Crowd-Sourcing

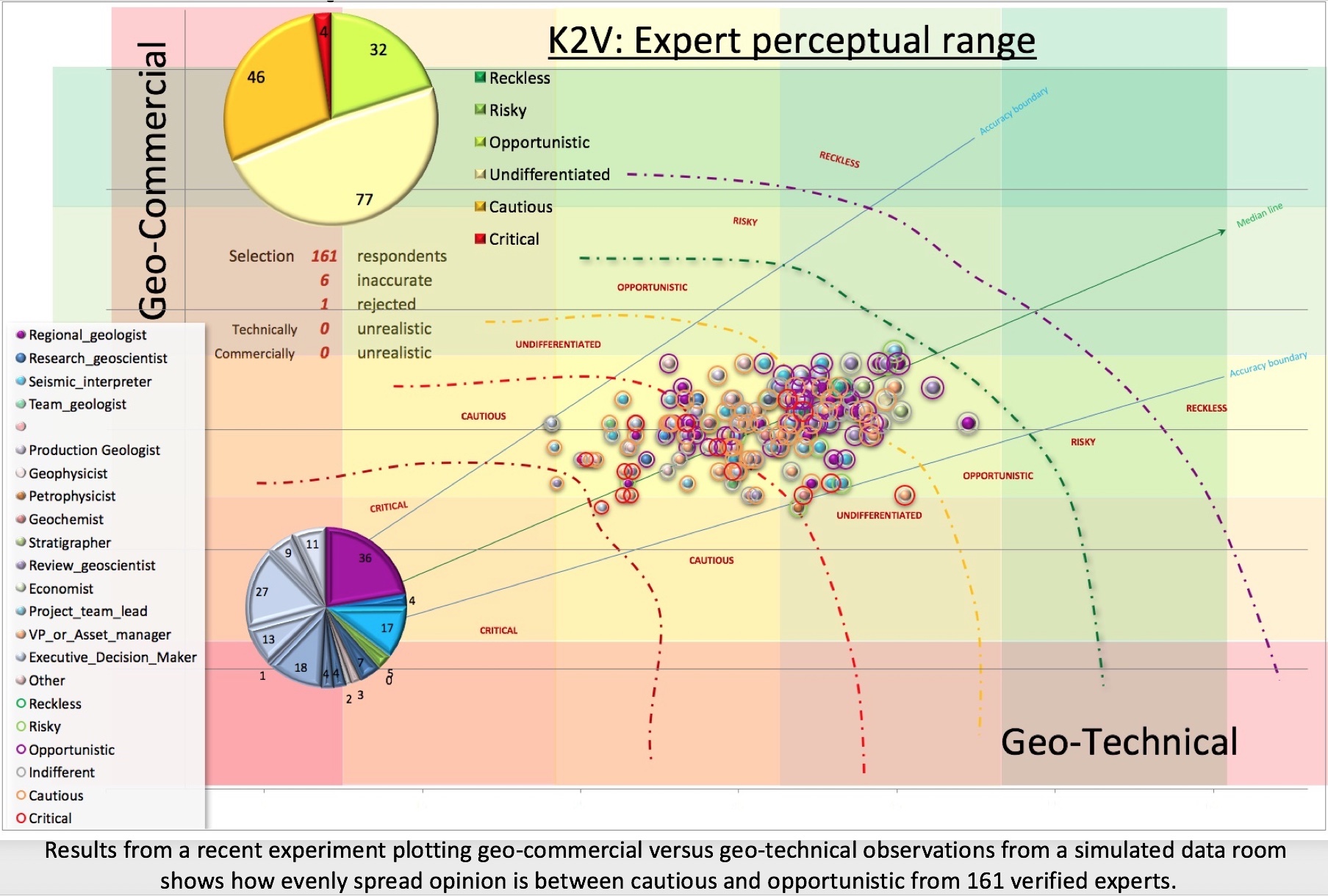

Crowd-sourcing techniques have been tried and tested in the North Sea by pioneering organisations such as Draupner Energy and Geonova. Focus to date has been to attract investment on individual opportunities which has demonstrated that crowd-sourcing opinion does work within the relatively limited range of interrogations used. Rose & Associates have done much to make the oil & gas sector think carefully about the dangers of cognitive bias and perceptual blindness [5]. In 2017, an experiment was launched using a simulated dataroom to establish if independent crowd-sourced opinion was capable of providing the means to mathematically collapse cognitive bias [6] in support of decision making. The challenge was to establish what size of population is needed to achieve a statistically valid result (ibid. critical mass). 350 geoscientists have so far participated in the experiment, which was supported by live lecture tours to a number of geology faculties and organisations around Britain. Participants were supplied with an information pack of three summary slides containing commercial background, play and prospect information, and were invited to role play. As with every data room, there were both gaps in information and an oversupply of detail in some areas. Participants were asked to indicate whether they would elect to participate in an opportunity (i.e. judgment or “gut feel”) and their responses were compared with a calculated value derived from 20 geo-technical and geo-commercial metrics (i.e.powers of observation - Fig. 2). Where individuals plot in Fig. 2 is still a guess but it is more accountable than the overall judgment because it is under-pinned by premises that we recognise. In effect, we establish the credibility of the whole by summing its parts and then comparing the two as separate perspectives to examine the differences (calibration).

Despite the complexity of informational challenges presented to participants in live sessions, it took them no more than 10-15 minutes to complete their observational scores, which appeared live on the presentation screen as they submitted their responses. Individual scores were measured against technical expertise and levels of experience, then compared with the actual outcome based upon a real opportunity. Different disciplines tended to demonstrate different biases but on the whole, the range of observational outcomes were strikingly consistent. Half of those who plotted in the neutral “safe” zone did so because they had insufficient information to polarise their view. Those who polarised their views were more prepared to tap in to their experience to overcome the gaps in information (exercising judgment) and often did so robustly but never exceeded the boundaries of possibility. What is less easy to explain is the disparity between how people reported their mood in conducting the survey and how their observational scores plotted. For instance, some people claimed that they felt “bullish” when doing the survey but their observational scores demonstrated that they were being “cautious”. The work has demonstrated that crowd-sourced opinion solicited in this way delivers results that are both rational and measurable. But there are many unanswered questions such as the gap between intuitive “gut feel” and their more analytical observations.

Total perceptual range for crowd-sourcing and live plenary dataroom simulations for a single opportunity. The size of the bubble is determined by the total score, the colour by “function in role” the colour of the “halo” by the mood claimed by the participant. The mood is also grouped in to class limits where the mid or neutral score is considered safe and varies from degrees of optimism (opportunistic, bullish or reckless) to degrees of pessimism (cautious or critical). Whereas "critical" implies that the opportunity is fatally flawed, neutral scores are sometimes attributed to “not having sufficient data to polarise their view”. Polarised views (cautious or opportunistic) favour declining or participating in an opportunity respectively. The top pie chart depicts calculated moods, the bottom pie the number of participants by role.

Knowledge Sharing

Applying value-driven observational scores to targeted participants using free online facilities like Knowledge PinMap™ opens up a whole new reference frame by consulting a broad, but anonymous, college of opinion.

Collective opinion can be achieved through open collaboration without compromising enterprise confidentiality if participants have been granted formal clearance from their respective enterprises, even if their submissions remain anonymous [3]. Collective opinion can then be associated with a compiled inventory of play potential across the North Sea entirely through crowd-sourcing [4]. Some see this as a “Mechanical Turk” approach by pooling knowledge to provide an enhanced play-based view that could not otherwise be achieved by machine learning. However you look at it, soliciting industry-wide knowledge has not been attempted before in the Oil & Gas sector and could play a key role in rejuvenating North Sea exploration.

The process has already begun, as knowledge holders have been invited to use the free online facility SpatialCV™ to stick a pin anywhere in the world where they have acquired knowledge in their careers, not just the North Sea [7]. Global knowledge is essential when bringing analogue content together for unproven plays in the North Sea. The identity of knowledge holders remains anonymous and will stay that way unless, in the interests of self-sovereignty, written consent is granted by a knowledge holder for a specific request for knowledge sharing. A list of bread-and-butter plays and potential plays for the North Sea are being compiled so that a match can be made between knowledge holder and play expertise. Those with the appropriate content knowledge will be invited to score each play using the 20 geo-technical and geo-commercial metrics indicated above. Once critical mass has been achieved (to collapse cognitive bias) play potential will then be ranked and the results published for all enterprise endeavours to feed back in to their business models. It is intended that in this truly open collaborative way, exploration could be rejuvenated in the North Sea, thereby accelerating further development.

Risk and Rewards

Fears about loss of competitive edge or lack of tangible reward, guarantee that initiatives involving open collaboration are more often doomed to fail. Proof of concept isn’t enough because in the end, if there’s “nothing in it for me”, why bother? If you are able as an organisation to acknowledge that there is more knowledge outside your organisation than there is inside, then having access to that pool has undeniable value adding potential.

The greatest effort comes not from companies, or even from ranking different plays. It comes from pinning your knowledge, which is a personal choice and not a corporate one, because pinners are not sharing what they know, simply that they know it. Making the effort demands personal gratification, a positive feedback loop. Pinning your knowledge for anyone to see gives you instant visibility, albeit anonymous by choice. By pinning your knowledge in “space and time”, you generate a spatial CV that tracks how your career has evolved through changing functions in role, recording expertise acquired along the way. Increasing your visibility is more than just career planning or an opportunity to find, or to be found. It is about having conversations with people who are genuinely interested in what you know. It doesn't matter whether you are already fully engaged or whether you are looking for that little bit extra from your working life: you have accumulated years of experience which makes you both unique, unprecedented, and interesting. You only have to want to share it in a way that makes it effortless for those who don't know what you know. If you find all of that attractive, then the reward is big enough to make open collaboration work. You can always collaborate for purely altruistic reasons because having conversations is not always about personal gain. It is also about belonging to a community and being able to give back. Perhaps all it takes to succeed is waiting for the right moment, when rewards outweigh the risks.

The Wood report [1] indicates that the Regulator should “facilitate and encourage collaboration on exploration”. This paper suggests going one stage further and provides the means for doing so, which could be facilitated by the regulator through encouraging “sharing knowledge and expertise” [1].

REFERENCES:

[1] Wood, Ian, 2014 – UKCS maximizing recovery review: Final report. (public domain)

[2] Loftus, Guy W.F., 2017 - Risk Optimisation (a ‘novel’ approach for frontier exploration). Geol.Soc.Lon conference “Managing Risks across the Mining and Oil and Gas Lifecycle”, July 2017

[3] Loftus, Guy W.F., 2018 - The tipping-point: "what you know will always get you more of what you want" - [LinkedIn article - https://lnkd.in/eTBNG4D]

[4] Loftus, Guy W.F., Burgess, Peter., Neal, Simon., Scardina, Allan D., 2018 - Sharing Knowledge for Value Creation [GEO ExPro in. press]

[5] Kahneman, D, 2011 – Thinking Fast and Slow. Farra, Strauss and Giroux, ISBN 978-0374275631

[6] Loftus, Guy W.F., Bloemendaal, S., Burgess P., Cleverley P. and Glass F., 2018 - Collapsing Cognitive Bias. [in. prep]

[7] www.k2vltd.com/article-12